When 35mm cameras arrived, focus was at first achieved by an accessory rangefinder fitted in what we now regard as the flash hotshoe on the top-plate. After establishing the subject’s distance, it was set on the lens.

Zeiss Contax then began to build the rangefinder into the camera body, coupling it to the lens, and speeding up focusing. This method became standard – and remains so today – on what are known as coupled rangefinder, or CRF, cameras. The Leica M series and Japanese Voigtländer cameras are the leading examples.

Zeiss Contax then began to build the rangefinder into the camera body, coupling it to the lens, and speeding up focusing. This method became standard – and remains so today – on what are known as coupled rangefinder, or CRF, cameras. The Leica M series and Japanese Voigtländer cameras are the leading examples.

Focus is achieved by turning the lens control ring: in some CRFs, the aim is to superimpose two views of the frame centre; in others, it is to align two views split across the middle. Most of the world’s iconic photographs – those that symbolise an era or stay in the memory – were taken with this type of camera. The subject is composed directly through an optical viewfinder, rather like a reversed telescope.

Some people believe this involves the photographer in the subject more than with a single-lens reflex camera, which momentarily blacks out the view. Most compact cameras also feature direct vision optical viewfinders, but these do not have the same viewing quality of an SLR.

Supporters of CRF and SLR types continue to debate. But taking a common-sense attitude, there’s little doubt that CRF works best with lenses of 35-90mm or perhaps even to 135mm. Shorter focal lengths need a supplementary viewfinder to show the wider angle of view. The longer focal lengths mask off too much of the viewfinder frame or need a magnifier to show it usefully. The 35mm, 50mm, 90mm and 135mm range is, however, the one used most by journalists and reportage photographers who like to work close in.

Yet a system that allows a lens of any focal length to be attached, and which fills the viewing frame with exactly what will appear in the recorded image, is perhaps always going to have greater appeal.

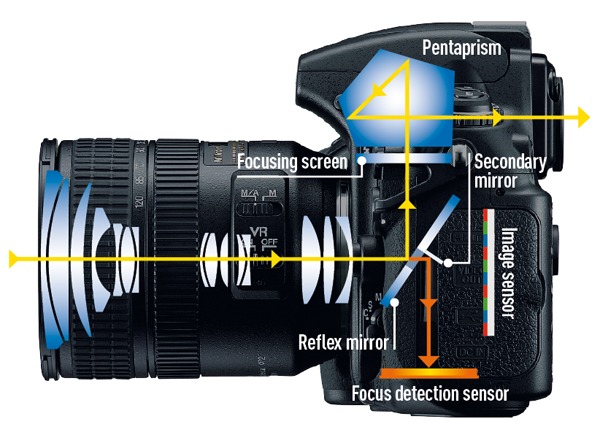

That is what the single-lens reflex camera does. The light travels through the lens and strikes a mirror angled at 45°C, reflecting the image up on to a screen. The overall distance from lens to screen is identical to that of lens to film or sensor. Therefore, any adjustments to focus on the screen correspond exactly to those that will be recorded in the image plane. When the shutter is released, the mirror momentarily flips up and out of the way, allowing the picture to be taken.

Image: The rays from the lens strike the reflex mirror and project upwards onto the focusing screen. This image is made upright and the right way round by the pentaprism, and viewed through the ocular lens. A part-reflective area of the reflex mirror allows a proportion of light to pass through to the secondary mirror, which reflects it down to the focus-detection sensors. The motor drives the lens to focus, the two mirrors swing up and the shutter is released, allowing all the light from the lens to reach the image plane.

Modern autofocus

Modern SLRs – a term that includes digital SLRs (DSLRs) – have the centre of the reflex mirror only half-silvered (or rather, half-reflectant).

This allows the rays from the lens to be split. Part is reflected up to the focusing screen while the rest goes through. There it meets a smaller, secondary mirror, which reflects the rays into the base of the camera’s dark chamber. There, detectors placed in the optical equivalent of the film or sensor plane can assess its sharpness and start the autofocus ability of the lens, or measure its strength and set the exposure.

Automatic focusing is a great step forward. For most work, the single-shot AF mode will work best. I was bred on cameras, whether CRF or SLR, in which you focus in the centre of the screen before reframing to compose the subject. Therefore, I usually choose a single autofocus zone in the centre or just above it, so that operation is the same. I don’t particularly want to interrupt my watching the subject by switching zones.

With more time and the camera in a fixed position, switching can often be helpful. On the other hand, when very close-up, it can be easier and more accurate to switch to manual focus.

Continuous or ‘servo’ automatic focusing comes into its own with moving subjects. The speed of modern chips allows the lens to remain focused on the subject as its distance changes and the camera is moved. Hence, it is also called ‘predictive’, ‘follow focus’ or ‘tracking focus’. You may find that if used on normal subjects it can get in the way, disturbing a focus set with quite small movements of the camera.

Live View

The latest chapter in the focusing saga is Live View. To my mind, the ability to inspect in real time the image as it will be recorded, brings the advantages of a large-format camera with its ground-glass screen to the SLR.

The latest chapter in the focusing saga is Live View. To my mind, the ability to inspect in real time the image as it will be recorded, brings the advantages of a large-format camera with its ground-glass screen to the SLR.

Plus, the ability to selectively magnify sections of the frame and manually adjust focus really brings the little cameras of today into focus as fully viable instruments.

Focus is the centrepoint of interest in a picture, but the next most important tool is the control of depth of field – how sharp subject areas appear both in front of and behind the subject. As always, it is those photographers willing to experiment who master the skills. Digital imaging allows us to experiment without cost.

Predictive focusing

1. The camera computer calculates the position the subject will reach by the time the exposure can be made, taking into account the delay while the reflex mirror rises

2. The drive motor moves the lens focus movement to give sharp focus at the predicted subject position

3. As the exposure sequence starts, the reflex mirror rises

4. The shutter runs just as the subject reaches the predicted position, making the exposure

Predictive AF

Image: Predictive AF enables the camera to adjust the focus of the lens to follow a moving subject as its distance from the camera changes. Though it is not infallible, when it works it results in a sharp sequence of images like these captured using a Nikon D300 and an 80-200mm f/2.8 lens.